Australian Cattle Dog history and breed development traces to the early 1800’s. They were bred and developed by the family of George Hall in and around Queensland and New South Wales, Australia. Without dispute, they are descendants of the wild Dingo. This is the story of the Hall family, the Hall’s Heeler, and the beginings of the greatest herding dog in the world.

A huge thank you to Noreen Clark, Michelago, New South Wales, Australia for this article on Australian Cattle Dog History, and for a peek into her new book A Dog For the Job, soon to be the ultimate resource on Australian Cattle Dog history and breed development.

Noreen is the author of A Dog Called Blue, the most researched and authoritative book on Australian Cattle Dog history.

Australian Cattle Dog History

The Kaleski influence on published Australian Cattle Dog history.

Most of what has been written and re-written about Australian Cattle Dog history can be attributed to the writings of Robert Kaleski (1877-1961). Some of it true, some not so much.

In this article Noreen gives us new insight into Australian Cattle Dog history and breed development, uncovered through her extensive research.

Kaleski and His Cattle Dogs

Kaleski, in 1903 and 1910:

In discussing Australian Cattle Dog history, Kaleski wrote:

“This breed was first made, as far as I can ascertain, by a Mr. Hall or Wall, of Muswellbrook,

about forty years ago. He imported the blue-gray Welsh merle for working cattle … but crossed them with the dingo, and founded the present variety, which, by selection and careful breeding, became a distinct breed and throws true to type …”

Robert Kaleski (1877-1961) was the first, and only, cattle dog fancier, to associate Thomas Hall with the cattle dogs that were so much a part of his own life. It was the one story that Kaleski stood by, although he varied it from time to time.

By the 1930s, it was Hall of Dartbrook, near Muswellbrook – but that was all he ever found out about the cattle dog’s origins or Australian Cattle Dog history.

Along with other dog world commentators of the time, Kaleski acknowledged the important contributions to breed development made by his friends, James H. (Harry) Bagust (1860-1914) and Harry’s son, George W. Bagust (1882-1935).

Kaleski was a writer, and a very imaginative one. He couldn’t resist telling a good yarn and he embroidered his cattle dog story with some highly unlikely “facts”.

That alleged Dalmatian infusion you may have heard about? Forget it.

Tom Bentley’s dog and the “Bentley mark”? The stuff of which legends are made and, like many legends, with no foundation in fact.

The distinctive speckle, however, of dogs such as Nipper, bred by Harry Bagust, set Kaleski to “burrowing” (his word) in British books on dogs, in the hope of finding a dog that could be the British ancestor of the speckled cattle dogs that he so admired: the working dog that, crossed with the dingo resulted in the Halls Heeler (Kaleski’s name for Thomas Hall’s dogs).

Kaleski’s burrowing was rewarded

Books, such as Dalziel’s British Dogs, described a mottled, smooth-coated collie, the Welsh heeler and so “blue-gray Welsh merle” was included in Kaleski’s Halls Heeler story.

“[The smooth coated colley is …] in all points, except coat … a facsimile of the more fashionable rough-coated ones, indeed, rough-coated and smooth-coated are often found in the same litter … The mottled, marbled, mirled, or Harlequin variety are nearly always smooth-coated … “the Harlequin or mottled dog is often termed the ‘Welch [sic] heeler’. The variety is, I believe, rather popular in Wales, but it is by no means confined to the Principality, but found scattered all over the United Kingdom.”

Vero Shaw’s Illustrated Book of the Dog also helped the story along. “There is one strain of smooth Collie which calls for particular attention, and that is the variety called sometimes the Welsh Collie, and at others the Highland ‘heeler’. In colour this dog is a peculiar sort of greyish hue, to which the term ‘harlequin’, ‘plum-pudding’, ‘tortoise shell’, are all applied.”

Stonehenge added to the story in his Dogs of the British Isles: “A mottled strain … is highly valued in the North of England and also in Wales.”

These references, from the British authorities, persuaded Kaleski that the Welsh Heeler was a recognised breed of dog and that the Halls’ import was a Welsh Heeler. He even hinted that the “Welsh heeler or merle” was known to him in the general working dog population in New South Wales and concluded that the Cattle Dogs bred by “Mr Hall of Muswellbrook” were originally a cross between Welsh merle and dingo.

(Kaleski made assumptions about Australian Cattle Dog history)

His assumptions were misguided. Kaleski’s understanding of “dog breeds”, c.1900 was quite different from dog breeds of c.1800. “Breeds”, as we understand them, didn’t really exist until well after the 1850s, when dog shows became part of the dog world, but “breed types” were common, and they did not always breed true to type.

…all that can be said of their British ancestor(s) is that it was a blue mottled, bob-tailed working dog, a drovers dog of some kind…

British working dogs were bred for function, not for appearance.

From what we know of the Halls Heelers descendants, all that can be said of their British ancestor(s) is that it was a blue mottled, bob-tailed working dog, a drovers dog of some kind.

Naturally bob-tailed working dogs, of no specific breed, are still to be seen in Britain and also farm dogs, that could be mistaken for Australian Cattle Dogs. Until rail transport displaced them, various kinds of drovers dog were used in Britain, to drive cattle from farm to market, often hundreds of head at a time, over hundreds of kilometres.

Kaleski remained the authority on cattle dog origins, regardless of how unlikely some of his ideas were, or how inconsistent his explanations. Even the Australian National Kennel Council perpetuated the Dalmatian myth.

Nothing more was heard of the Halls Heelers until 1990 when Over-Halling the Colony was published. This collection of essays on George Hall and his family is informative about the Halls but not their dogs.(A chapter on them has since been found to have been based on incorrect assumptions.)

Australian Cattle Dog History

Australian Cattle Dog History and The George Hall Family

The Halls Heeler story is, however, an important part of the story of George Hall and his family and particularly of Thomas Simpson Hall, George’s fifth son.

Most children in England left school at the age of twelve, when George Hall was a boy, but George was encouraged to attend night school for another two years. When he was fourteen, he was apprenticed as a carpenter and joiner.

Later he completed another apprenticeship, in agricultural machinery. With these trade skills to recommend him, he made his way to London.

A housing shortage in London was to his advantage and he was able to build under lease agreements, making him landlord as well as builder.

By 1791 his finances were sufficient to support a wife and he made a hurried trip home to marry Mary Smith.

All was not well in London, however. The emergence of workers’ groups (early trade unions), riots against oppression by vested interests, rising inflation, and manipulation of food and commodity prices did not promise well for the future.

He gave thought to the New South Wales colony, settled since 1788. The young colony was in need of men with trade and farming experience and the British government offered free passages to suitable immigrants.

George applied in 1801, as did others from their church congregation. This group later became known as the Coromandel Free Settlers, identifying with the ship on which they sailed.

George, Mary and their children left England on 12 February 1802 and arrived in Sydney on 13 June.

The Sydney of 1802 was only a few hectares in area. A squalid little settlement, it huddled around Sydney Cove and the Tank Stream, its water supply. Livestock wandered its streets and the dog population had reached nuisance levels.

The ancestors of the Halls Heeler would later be found among these dogs.

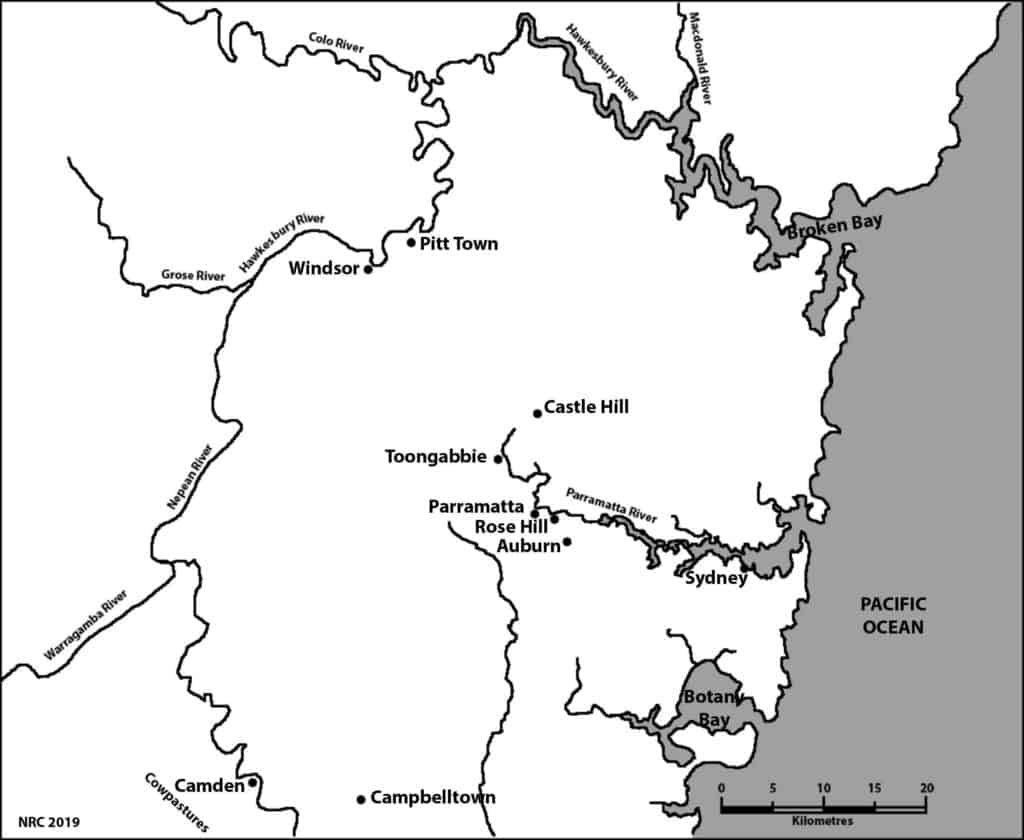

George, and the other Coromandel settlers were granted land at Toongabbie but their land was already farmed to exhaustion. They complained, with success, and were given new grants in the Hawkesbury Valley, on the northwest fringes of the settlement. George’s first Hawkesbury grant, in 1803, was 100 acres (40 ha) and two sheep.

He and his household were entitled to be “on stores” for three years, that is, to receive government supplied victuals, but by 1805 his grant was self-supporting, and by 1821 he had increased his land holdings, by purchase, to 1,500 acres (607 ha). Available land in the Hawkesbury Valley was running short, however, and there was not much more room left for George.

During 1819 and 1820 John Howe, one of the Coromandel settlers, led the expeditions that found a way from the Hawkesbury to the Hunter Valley: Howe’s track, later known as the Putty Road. The road opened to traffic in 1823 and George applied for land in the Upper Hunter Valley for himself and four of his sons (including Thomas) two years later.

The Halls were granted 4,040 acres, including Dartbrook, Thomas’s future home. Other acquisitions followed. By the time George died, in 1840, the Halls held some 36,000 acres (14,570 ha) in the Upper Hunter Valley.

Thomas Hall settled at Dartbrook in 1825 or 1826. By 1828 he was in charge of 4,700 acres, 700 cattle, 2 horses and 8 convict workers. He would have made the 300 km journey from the Hawkesbury Valley to Dartbrook on foot, with a couple of horse-drawn carts to carry stores for the journey and tools for use in building, housing, stock yards and fencing.

With him went his assigned convict workers and his brothers, Matthew and Ebenezer, who also had land grants in the Hunter. Thomas undoubtedly took cattle, too, on his first journey to Dartbrook. There were several men in the party and that number could have driven a mob of forty or fifty head, or more.

Dogs? Of course there were dogs in the party. Dogs were an integral part of nineteenth life, particularly of rural life. Whether George Hall chose dogs, or whether stray colonial dogs chose him, is immaterial.

(Yet they played an important part of Australian Cattle Dog history)

Dogs would early have been a part of George’s household and some of the family’s dogs would have accompanied Thomas to the Hunter. Those that proved themselves, working Thomas’s cattle day after weary day along the Putty Road, would have been kept in mind for future breeding. (These dogs were the “imported” ancestors of the Halls Heeler to which Kaleski referred.)

Later on, breeding from the dogs that had proven themselves on the trek to Dartbrook would become one of Thomas’s responsibilities.

Thomas’s dog- (and cattle-) breeding practices would have been less rigorous than those of a present day kennel or stud breeder. He mated best to best, but without detailed record keeping. The dingo infusion(s) was probably casual, too, but Thomas was an intuitive animal breeder, attuned to recognising valuable traits in his stock when they appeared – as obviously they did.

Australian Cattle Dog History

Australian Cattle Dog History Shows That The Halls Heeler began to emerge some time in the late 1820s.

Need for them became extreme during the 1830s. The phasing out of convict transportation foreshadowed labour shortage and the Halls would become increasingly dependent on their own family members, and particularly on their dogs, as their land holdings increased.

George died in 1840 but the same sort of cooperation, that had existed between family members during his lifetime, continued. William and Thomas managed the enterprise and, in the name of the George Hall Estate, extended its holdings as George would have wished. They increased their holdings in the Hunter Valley, moved into the New England region, and further north, into Queensland.

The Halls’ stations were close enough to one another for stock to be moved easily from station to station, and for stockmen to travel between station and station when cattle work (mustering, branding) needed extra hands. It was a Hall family boast, that they could travel from Queensland to the Hawkesbury Valley and camp on their own lands every night.

The properties were selected with an eye to access to the three main markets of the 1860s: Sydney, Brisbane and Newcastle. The Halls’ properties fanned outwards from Dartbrook and increasing distance between them forced decentralised, but cooperative, dog breeding. Practices still followed in western New South Wales were probably those of the Halls and their stockmen.

Each of the various stations kept dogs of one sex, only. This avoided fights and the obvious distraction offered by a bitch in heat. When a mating was intended, the necessary arrangements were made and pups supplied where needed. Over-supply of pups was unlikely. Injuries inflicted by cattle would have accounted for many deaths; so would parasite infestations and the inevitable snakes.

The Halls Heeler travelled. From his nominal origin at Dartbrook, he spread through the Hunter Valley, north into the New England region of New South Wales, further north into Surat in Queensland, and beyond. He travelled wherever the Halls and their stockmen needed him.

Thomas Hall died in 1870 and William Hall, in 1871. Properties owned or leased in the name of the George Hall Estate were sold. The Hall family faded from the rural scene and so did the Halls Heeler, but in name and ownership only.

Stock and land were sold together, Some of the station hands and stockmen stayed on the stations, under new ownership and with them, their dogs. Some of them took up property on former Hall stations when these were subdivided. Others moved on, taking their dogs with them. The dogs became freely available and some became associated, in name, with particular stockmen such as John Timmins and his “Timmins Biters”.

The greater part of the George Hall Estate holdings was in leased runs in the New England region of northern New South Wales and in Queensland. Because of their remoteness from Dartbrook and the Hunter Valley, two Halls Heeler populations developed, that were only distantly related.

The most significant difference between the two populations was breeder acceptance of stumpy tails and litters that included both long-tailed and shorttailed pups. Queensland breeders took the presence or absence of tail for granted. Short-tailed cattle dogs were also known in northern New South Wales but in Sydney, under the influence of Kaleski’s breed standard, shorttailed pups may have been culled as defective – which they are.

Kaleski credited the wholesale butcher, Alexander Davis, with having brought Halls Heelers to Sydney, from the Hunter Valley during the 1870s. Davis may have done so but Halls Heelers must have been in Sydney much earlier, working stock on the Halls’ Auburn Farms and driving stock from Pitt Town to Auburn.

Australian Cattle Dog History-Early Breeders

Between World War I and World War II, the Australian dog world was in disarray. Competing dog clubs vied for supremacy and the Cattle Dog world, itself, was in no better position. The absence of an agreed, and generally implemented, breed standard and uncontrolled judging had its effect on the Cattle Dog breed.

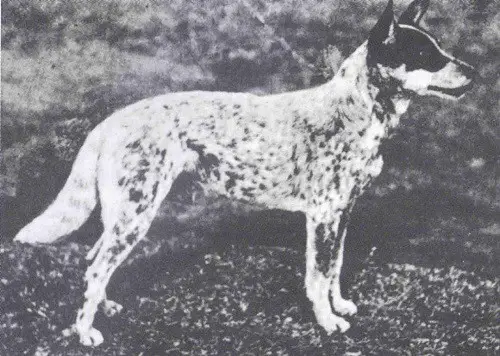

The photographic coverage, particularly in the Sydney Mail from between the two wars, documents changes in type. Two forms were developing. The first, a lean, leggy dog, reminiscent of Nipper, and a second, a heavier-bodied, shorter-legged dog.

Compare the lean, leggy Kalamunda Rex Regis [1949], with the heavy bodied, short-legged Bobby Blue [1944]. That is, there were recognisable sub-types within the breed type as set out in the Breed Standard (type-within-type). Kaleski described the heavier–bodied, short-legged dogs as “piggy”. (Year of birth given in square brackets.)

Hailed as “Father of the Breed”, Little Logic [1939] was born and exhibited during the World War II years. Only one photograph of the dog survives but it shows him to be of the lean, leggy type. By the end of the 1950s, Little Logic was in the pedigrees of most registered Australian Cattle Dogs but usually by way of Logic Return [1949] – a typical exemplar of the “heavier-bodied shorter-legged” sub-type.

The influential Wooleston Kennels emerged during the 1950s. Bernie and Berenice Walters chose Broombees Bobby (a direct Little Logic descendant) and Turrella Blue Lass (a Logic Return descendant) as the basis for their breeding program.

This combination produced Wooleston Blue Jack [1954]. Nearly all Wooleston dogs and most, if not all, Australian Cattle Dogs whelped since 1990 are descendants of this dog.

According to Berenice Walters she and Bernie aimed towards breeding Australian Cattle Dogs that were successful, both in the breed ring and as workers. Turrella Kennels (Sydney) was a bench kennel but W. Roth (Broombees Kennels, Mudgee, NSW) is said to

have been a drover. In breeding from Broombees Bobby and Turrella Lass, both Wooleston aims were realised.

For some twenty years, Wooleston Kennels supplied breeding stock to kennels in Australia and overseas. Over thirty-five championship titles are credited to Wooleston, from Australia and overseas, and there was a ready market among local stockmen for dogs that were not of show quality.

Breeders of the 1950s seemed to want either Logic Return offspring or a pup from Wooleston Kennels. This changed the direction taken by the breed. The heavier-bodied shorter-legged form prevailed and was further consolidated, from the 1970s, by Tallawong Kennels.

From their start in the late 1960s with Wooleston Blue Jenny as foundation bitch, Ken and Helen Dickson bred into Wooleston by purchase of other bitches and stud use. By the end of the 1970s, Tallawong was, effectively, a closed kennel. Non-Tallawong names appearing in later Tallawong pedigrees are those of dogs with strong (or exclusive) Tallawong ancestry.

No other Australian Cattle Dog kennel in Australia has operated with so single minded an approach. Between 1990 and 2000, over 90% of all “successful” Australian Cattle Dogs (that is, dogs that were used for breeding) were descendants of Wooleston Blue Jenny.

Australian Cattle Dog History

The Australian Cattle Dog and the Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog share a common origin

. The two began to diverge c.1850 when distance separated Halls Heelers on the George Hall Estate holdings in New England and Queensland from their parent stock in the Hunter Valley.

Differences only became apparent when Cattle Dogs became a bench breed in the 1890s. Breeders exhibiting in Queensland accepted short-tailed Cattle Dogs and litters that included both long-tailed and short-tailed pups.

In Sydney, under the influence of Kaleski’s breed standard, short-tailed pups may have been culled as defective – which they are – and were not seen in the show ring.

A review of litter registration procedures in Queensland, during the 1950s, revealed embarrassing anomalies. In a hasty and ill-considered response, the Canine Control Council de-registered all breeders of short-tailed Cattle Dogs. One of them, Iris Heale, Glen Iris Kennels, was successful in reversing de-registration and became the only remaining breeder of short-tailed Cattle Dogs.

The short-tailed Cattle Dog, as a bench breed faced extinction but was rescued in 1988, when the Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog Redevelopment Scheme, was inaugurated by the Australian National Kennel Council.

Almost an accident of Australian Cattle Dog history, but the Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog has developed independently of the Wooleston and Tallawong influence, that has shaped Australian Cattle Dog type since the 1960s.

© Noreen Clark 2019

Australian Cattle Dog History-References

References

Clark, N. R. 2003. A Dog Called Blue: the Australian Cattle Dog and the Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog 1840-2000. WriteLight for N. R. Clark.

Clark, N. R. [in prep.] A Dog for the Job.

Dalziel, H. 1879? British Dogs: their varieties, history, characteristics, breeding, management, and exhibition. TheBazaarOffice.London https://archive.org/details/

britishdogstheir00dalzrich/

Hancock, D. 2014. Dogs of the Shepherds: a review of pastoral breeds. Crowood Press,, Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wilts.

Kaleski, R. L. Cattle Dogs and Sheep Dogs, p. 6. Farmers Bulletin 38. New South Wales Department of Agriculture, 1910.

Shaw, V. 1881. The Illustrated Book of the Dog. Cassell, Petter, Galpin, London. https://archive.org/details/ illustratedbooko00shawrich.

Stonehenge (pseud. of J. H. Walsh). 1882. The dogs of the British Islands, being a series of articles on the points of their various breeds, and the treatment of the diseases to which they are subject. 4 th ed. Horace Cox, London. https://archive.org/details/

dogsofbritishisl00walsrich/

Warner, R. M. [ed.] Over-Halling the Colony: George Hall, Pioneer. Australian Documents Library, Sydney, 1990.